Potential contribution of biogenic materials in new and renovated buildings towards carbon budgets and storage in Switzerland

In the current climate urgency, reducing greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions is slowly becoming a priority in the political agenda of many countries (Shukla et al., 2022). Net-zero goals by mid-century are mentioned in most national strategies of the signing parties of the Paris agreement (Framework Convention on Climate Change, 2021) while carbon budgets (allowances of CO2 emissions tied to specific degrees Celsius of global warming and probabilities of achieving them) to remain within acceptable ranges of global warming are not yet widely used in official pathways to net-zero (Steininger et al., 2016). Although the global goals are clear, a lag in implementation strategies is also evident (Shukla et al., 2022). The struggle lies in shifting current practices, social norms, and investments towards climate neutrality fast enough to keep anthropogenic CO2 emissions below the global carbon budget threshold (Williges et al., 2022). The speed at which we need to act reinforces the importance of deploying and enabling existing solutions and mechanisms that allow a drastic reduction of CO2 release in the atmosphere within mid-century while ensuring their long-term sustainability through technological and economic developments. Although drastic reduction of CO2 emissions remains the number one priority, it becomes more and more evident that we will also need to rely on effective CO2 sequestration and storage to stabilize global temperature increase at a sustainable range (Shukla et al., 2022).

Within this context, the building sector is a known major contributor to GHG emissions and one that struggles to rapidly shift to low-carbon practices (Cabeza et al., 2022). The sector is heavily dependent on fossil fuels to operate its buildings (IEA, 2023) and cement and steel to expand the stock, which alone contribute to 15 % of global GHG emissions (Bajželj et al., 2013). Although a great variety of opportunities are already available to practitioners to employ low-carbon alternatives (Habert et al., 2020; UNEP, 2023), strong barriers in the widespread implementation are yet to be overcome (Mata et al., 2021).

In recent years, an additional opportunity for the building stock to have a positive impact on climate is being discussed in the literature (Ichioka and Pawlyn, 2021). The strategy is to use buildings as an overground carbon pool (as trees in the forest), thereby preventing CO2 emissions from being released into the atmosphere (Churkina et al., 2020; Suttie et al., 2017). This concept finds its relevance in using the naturally effective biogenic carbon pump. A system that is effective as long as the inflow from biogenic carbon within the built environment is bigger than the outflow coming from the end of life of biobased building materials through replacements and building demolition (Mishra et al., 2022). In such setting, the building stock is seen as an additional carbon reservoir from biosphere, geosphere, ocean and atmosphere with its own dynamic and carbon residence time (Smith et al., 2016). Adding biogenic material within such reservoir creates a net-positive system (inflows > outflows in the biogenic carbon cycle) as long as the inflow is kept constant or increased during the examined timeframe (Mazelli and Bocco Guarneri, 2024). Considering the nearly linear relationship between CO2 atmospheric concentration and temperature increase (Cline, 2020), delaying the outflow of biogenic carbon will, in the examined timeframe, reduce the CO2 concentration in the atmosphere thus reducing the peak in global temperature increase (Matthews et al., 2023). Reducing the peak is of major importance to avoid the set-off of irreversible impacts on the climate (IPCC, 2021). Postponing emissions could also prove very useful to buy some more time to develop and deploy the awaited technologies that would stop the biogenic carbon outflow by capturing carbon during or after combustion (Minx et al., 2017).

Unlike carbon flow analysis at the building stock level, where material flow analysis is an established method, assessing the potential of storing biogenic carbon at the individual building scale remains a debated topic (Hoxha et al., 2020; Ouellet-Plamondon et al., 2023). The limitations of scale and timeframe introduce greater uncertainties. However, it is crucial to develop appropriate tools and incentives at the building scale to enable practitioners to design buildings that align with climate goals.

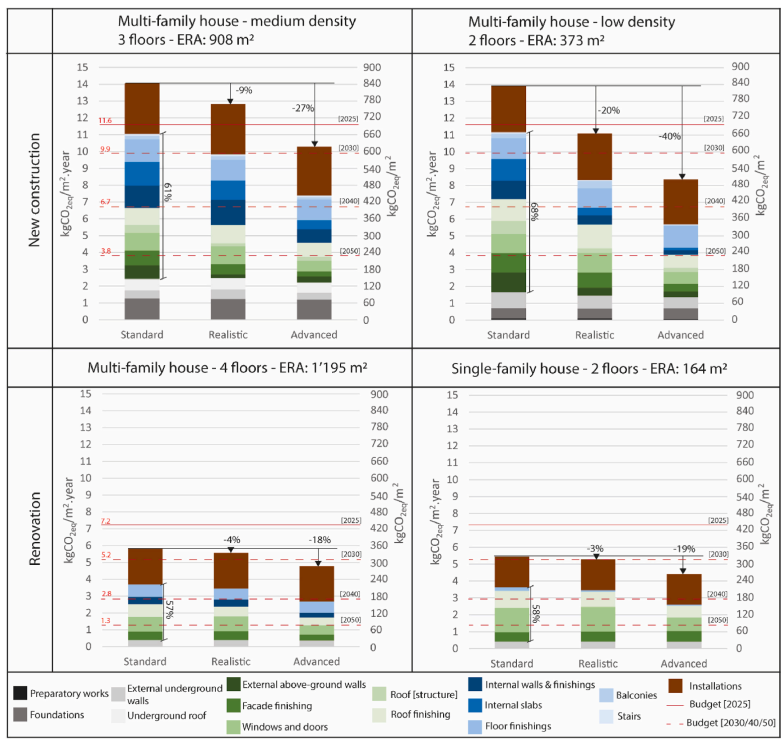

Bio-based construction materials are derived from biomass and usually require less or low-energy processing to be produced (Sutkowska et al., 2024; Suttie et al., 2017). Additionally, their biomass composition makes them natural carbon stocks with CO2 being sequestered during their growth (Harris et al., 2018). For these reasons, bio-based materials are the ideal candidates to tackle both climate goals (i.e. reduce emissions and sequester and store CO2) in the built environment. Bio-based materials at building scale are discussed in the literature for their potential to reduce global warming through biogenic carbon storage according to different accounting methodologies (Arehart et al., 2021; Göswein et al., 2020; Guest et al., 2013a, 2013b; Hoxha et al., 2020; Pittau et al., 2018, 2019), but the primary benefit of these materials is their lower GHG emissions in production compared to standard construction materials. Several studies conducted comparative life cycle assessment (LCA) at building scale to demonstrate the lower impact of bio-based materials compared to conventional construction materials (Andersen et al., 2021; Attia, 2016; Carcassi et al., 2022; Galimshina et al., 2024; Göswein et al., 2021b; Kumar et al., 2024; Mouton et al., 2023; Pierobon et al., 2019; Younis and Dodoo, 2022). However, a meta-analysis of 44 LCA studies indicates that while bio-based materials frequently offer GHG emission savings, they may also lead to increased impacts in other indicators such as eutrophication, ozone depletion, and land use (Weiss et al., 2012). These findings highlight that the environmental performance of bio-based materials is not universally better and depends strongly on system boundaries, agricultural practices, and end-of-life assumptions. Recent studies have also further highlighted the importance of the temporal dimension in carbon accounting. Hawkins et al. emphasized the significance of timing in carbon fluxes and its influence on climate impact assessments (Hawkins et al., 2021), while Craft et al. introduced the concept of temporal net-zero embodied carbon, arguing for more dynamic approaches that account for emissions and sequestration timing over the life cycle (Craft et al., 2024). Furthermore, Andersen et al. examined the challenges and inconsistencies in current biogenic carbon accounting practices in LCA, underscoring the need for transparent methodologies and harmonized conventions (Andersen et al., 2021). These insights underline the relevance of integrating time-dependent effects when evaluating the climate benefits of biogenic materials. Within this context, this research tackles the following main questions: is an increased share of biogenic materials at building scale sufficient to stay within specific carbon budgets? Additionally, is the biogenic carbon content, intrinsic to biogenic materials, a relevant potential to release pressure on the stringent targets?

This paper explores the potentials and implications of increasing the amount of biomass in new and renovated buildings in terms of fossil GHG emissions and biogenic carbon storage in the frame of our climate targets and mid-century commitments. The following research questions are challenged: what are the potential reductions in embodied GHG emissions attainable by an increased use of biogenic materials in future new buildings and refurbishments? And what can’t be reduced? Which building characteristics or requirements affect this potential? How much biogenic carbon can be stored by an increased use of biogenic materials? Is it a relevant quantity? Where in the building is this carbon mostly stored? Which component(s) are the most effective in reducing GHG emissions while maximising long-term storage of biogenic carbon?