PLATO Contemporary Art Gallery/

KWK Promes

Project Details

Location(City/Country):

Ostrava / Czech Republic

Tipology:

Transformational use

Year (Design/Construction):

- / 2024

Area (Net/Gross):

2841 m2 / 3601 m2

Operational Carbon emissions (B6) kgCO2e/m2/y:

-

Embodied Carbon emissions (A1-A3) kgCO2e/m2:

-- Transformational use of a derelict building bringing back to life

- Transformation of space around the building into a green biodiverse space

- Reuse of bricks from the areas previously demolished due to lack of maintenance

- Exhibition rooms are finished with white lime plaster laid over mineral board insulation.

By saving a historic building and turning it into an art gallery, we introduced a solution that makes art more democratic. Thanks to the revolving walls, it goes outside the building in an unusual way. We transformed the space around the gallery, which was previously contaminated, into a biodiverse art park for the benefit of the residents.

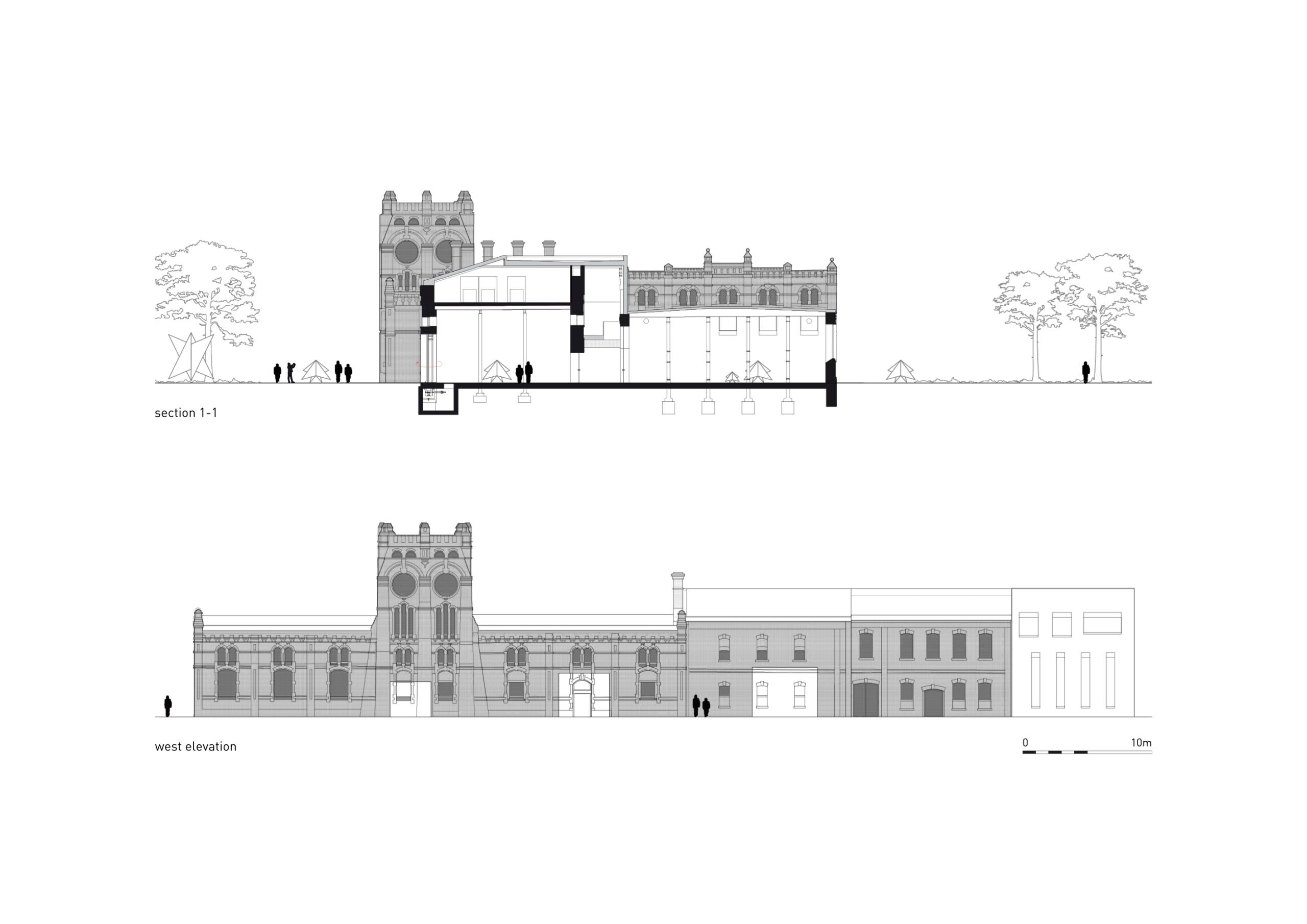

GENESIS + IDEA

The realization is the result of an international competition to transform a dilapidated old slaughterhouse in the Czech city of Ostrava into the PLATO Gallery of Contemporary Art. The walls of the slaughterhouse were dilapidated and battered in many places by huge holes. The sooty brickwork bore witness to the city’s industrial history. We took these deficiencies at face value and added another layer to the history of the building, which is under conservation protection. We were allowed to preserve the character of the soiled brick and the windows, and to fill in the openings in the walls with contemporary material while retaining the old ornamentation of the brick walls. We also used the principle of recreating all the non-existent elements of the building from micro-concrete to rebuild a section of the slaughterhouse that did not survive the start of construction.

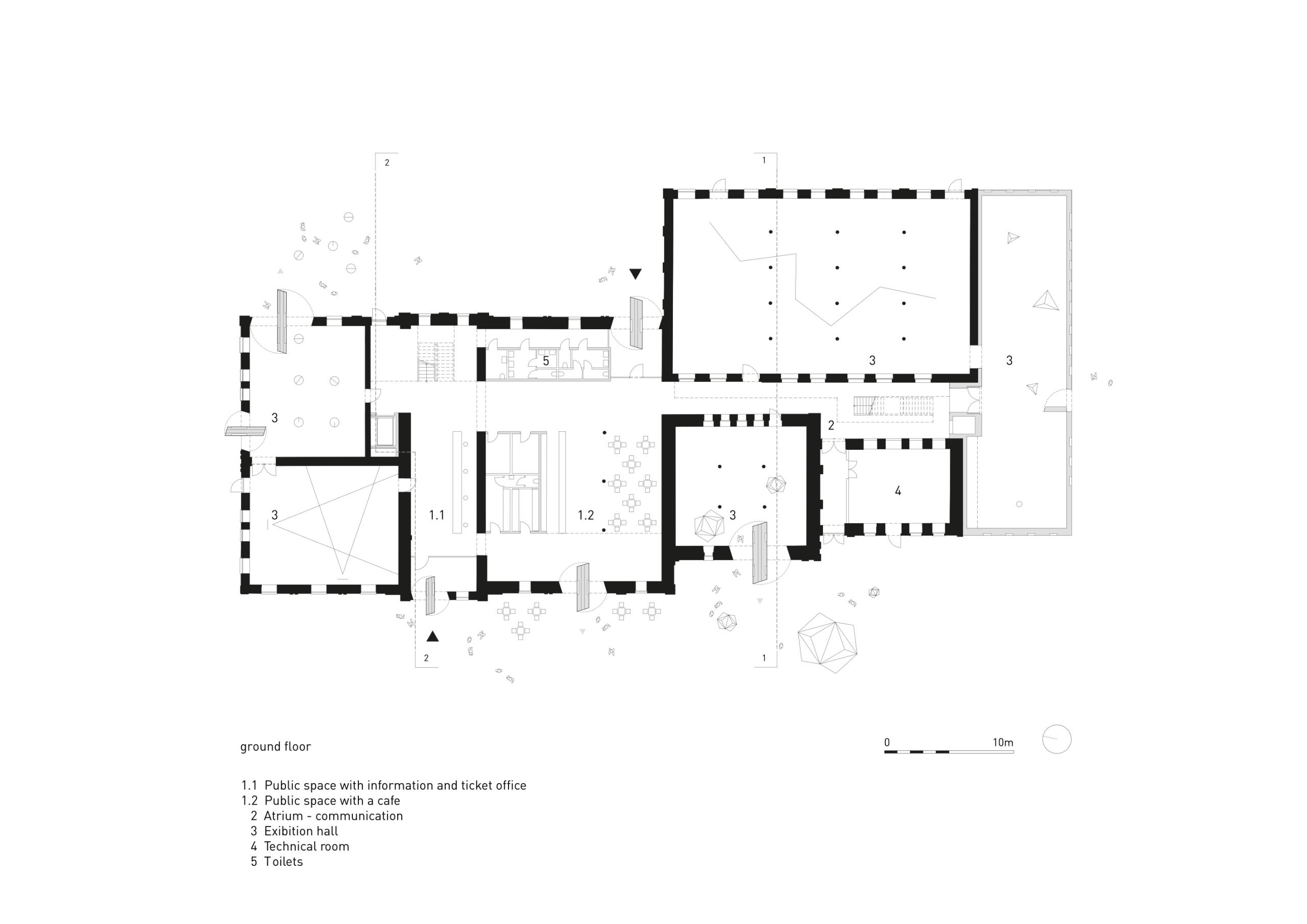

The main idea of the project is based on preserving the functionality of the openings as shortcuts connecting the building to the city. Hence the idea that their new infills could rotate and open the exhibition halls directly to the outside. This has provided artists and curators with entirely new exhibition possibilities and allows art to literally ‘go out’ into the space around the building. Mobility has meant that culture in the broader sense has the opportunity to become more democratic, as well as accessible to new audiences.

We became involved not only in saving the former slaughterhouse building, but also in the design of the outdoor areas, even though this was not our task. Initially, we imagined a paved surface there for artistic activities, but as we got to know Ostrava better, we realised that the place was more in need of attractive green space for residents. The contaminated soil there has been rehabilitated and replaced by a biodiverse park with water-permeable floors, flower meadows and with retention basins. The layout of the greenery refers to the location of the buildings that once supported the slaughterhouse, and edible crops, also inside the gallery, complete the transformation of the site. An inclusive space has been created, sensitising not only to art but also to environmental issues.

The life of the park is a process that has been planned over the years, going on in a sense on its own terms. Although we don’t really have any influence on its final appearance, we have seen great value in what has happened here. A community of people has formed around the gallery, actively participating in the process of creating it, and we have come to understand that by giving the field to others, there is a real commitment to be gained. The typical sterility here has been replaced by an engaging aesthetic, where process and participation are paramount. This also applies to the interior of the gallery, which largely lives its own life, making this elitist function much more egalitarian.

STRUCTURE

The original, dominant material of the building is brick (of which it was built). The deteriorated bricks have been mostly replenished with those recovered from a collapsed section of the building. The new glazing has a ceramic screen print, making it appear dark and dull, attenuating the light in the galleries. The abattoir’s interiors were whitewashed with lime for hygienic purposes, so the exhibition rooms are finished with white lime plaster laid over mineral board insulation. The soiled brickwork inside the building appears in the former atrium, which, after roofing, became the link between all gallery spaces. The wooden roofs covered with dark felt have deteriorated and have been replaced with steel structures and covered with a light-coloured membrane. As a result, the roofs heat up less, without creating a heat island effect around them. The colour refers to the micro-concrete from which all the new and reconstructed elements are made. The most important of these are the six rotating walls, two of which are entrances to the building and the others connect the galleries to the surroundings. When closed, the walls become an extension of the exhibition area. Retaining the ornamentation proved to be a very pragmatic solution, as it allowed the gates to adapt to the varying thickness of the brick walls. Despite their considerable size, when closed they provide a complete seal, and servicing the mechanisms hidden under the floor is simple and required once a year. The tower was the location of installations related to the operation of the slaughterhouse. We have retained its original purpose so that the installation elements do not interfere with the historic facades and smooth roofs.

EPILOGUE

During the redevelopment, the PLATO gallery was temporarily housed in the neighbouring Bauhaus building – a former DIY store. With the abandonment of the Bauhaus comes the question of its future and how to deal with such buildings. We decided that we would fight for this space in the same way that we fought for the space around the former slaughterhouse. That is why we started a long process, similar to the one initiated many years ago to save the buildings of the revitalised slaughterhouse.

- Office: Robert Konieczny KWK Promes

- Authors: architects Robert Konieczny, Michał Lisiński, Dorota Skóra

- Author Cooperation: architects Tadeáš Goryczka, Marek Golab-Sieling

- Collaboration: architects Agnieszka Wolny-Grabowska, Krzysztof Kobiela, Adrianna Wycisło, Mateusz Białek, Jakub Bilan, Wojciech Fudala, Katarzyna Kuzior, Damian Kuna, Jakub Pielecha, Magdalena Orzeł – Rurańska, Elżbieta Siwiec, Anna Szewczyk, Kinga Wojtanowska, Karol Knap

- Structural Engineers: MS – Projekce Ing. Jaroslav Habrnal, Ing. Petr Hanko

- Building Services Engineers: MS – Projekce Ing. Jaroslav Habrnal, Ing. Petr Hanko

- Landscape Architect: Denisa Tomášková

- Interior Design: Robert Konieczny KWK Promes, TUKEJ Justyna Kucharczyk, Agnieszka Nawrocka, Yvette Vašourková CCEA MOBA

- Client: Statutory City of Ostrava

- Photography: Juliusz Sokołowski, Jakub Certowicz, Viktoria Tymanova, Ostrava City archive, KWK Promes