Business Models for the Circular Economy — and Which Make a Difference

News Detail

Source:

Network for Business SustainabilityCompanies have choices when they enter the circular economy. Learn which business models make economic and environmental sense.

“The Basics” provides essential knowledge about core business sustainability topics.

There are many ways to approach the circular economy. But they’re not all created equal.

Different business models have different impact for profits – and for sustainability.

This article lists the options for circular economy business models and compares the impact of each.

It draws on work by researcher Nancy Bocken (Maastricht University) and her colleagues. Over a decade, they’ve examined the circular economy from every angle: economic, social, political, and environmental.

The article describes:

- Four main categories of circular economy strategies

- Specific business models associated with each

- The economic and environmental case for different circular economy business models

- The “best” choice for the environment

As your company engages in the circular economy, use this article to help focus your efforts.

What Is a Circular Economy Business Model?

A business model is the fundamental way that a company creates, delivers, and captures value.

The circular economy aims to reduce waste and resource use by rethinking every aspect of a product’s life cycle.

Circular business models thus try to find economically viable ways to continually reuse products and materials, using renewable resources where possible (as Bocken and colleagues wrote in a 2016 paper).

These solutions are important because our current economy is hard on the planet. Globally, natural resource use has more than tripled globally since 1970 and keeps growing, according to the International Resource Panel. Resource extraction and processing cause more than 90% of biodiversity loss as well as huge climate impacts.

“Incremental” or “Transformational” Circular Economy?

While many companies have made commitments to circularity, most are pursuing relatively minimal changes, reported a recent Bain study. These companies focus on recycling or waste management rather than more significant changes.

“The circular economy may well be at an important crossroad,” Bocken and colleagues Laura Niessen and Sam Short wrote in 2022. “It can continue to propose incremental changes to resource flows, leaving the wider, unsustainable, economic system unchanged, or it can join a transformative movement toward a sustainable circular society.”

Here’s the core question: How do different circular economy business models meet economic and environmental goals?

Four Circular Economy Strategies and Related Business Models

From: Bocken, N., Stahel, W., Dobrauz, G., Koumbarakis, A., Obst, M., & Matzdorf, P. (2021). Circularity as the new normal: Future fitting Swiss business strategies. PwC Switzerland.

First, what are the different options for circular economy business models?

The circular economy gets its name because it tries to keep resources in a “loop.” The goal is to keep the same resources in the loop as long as possible — by reducing the need to bring in new material, and by reducing the amount of waste leaving the system.

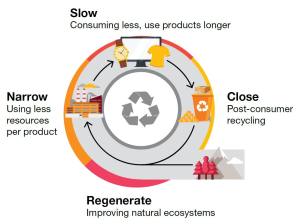

There are four strategies for supporting this loop, each with related business models. This graphic shows them.

4 Circular Resource Loop Strategies

Narrow the Loop

The strategy of “Narrowing” means that fewer resources enter the production loop. That can happen through efficiency, by using fewer resources to create a product. If your company has invested in actions like reducing energy use, saving water, or making products lighter, you’re already narrowing the loop.

Another “narrowing” approach is substituting unsustainable materials with greener alternatives. Switching to renewable energy is a common example.

Common “narrowing” business models maximize resource efficiency. For example, lean manufacturing aims to eliminate waste. Often associated with the Toyota production system, lean practices try to reduce any excess use of resources.

Close the Loop

“Closing” the loop is most associated with recycling waste, both during the production process and after consumer use. Formal business model terms are “extending resource value” and “industrial symbiosis.” Both turn waste into value by keeping resources in the system.

Paper, metal, and glass recycling are already common, though they can be increased by new collaborations and take back systems. “Industrial symbiosis” finds more ways that industrial outputs can be exchanged, either inside a single company or industry or across multiple industries. A China manufacturer might sell its broken pieces to a brick maker, for example. British Sugar developed animal feed from by products and used excess heat to power greenhouses.

Slow the Loop

“Slowing” the loop keeps resources in the economy by reducing unnecessary consumption, extending product life, and enabling reuse.

A common business model is “Product Service Systems.” These provide services to satisfy users’ needs so that they don’t need to own products. For example, stroller company Bugaboo has a stroller lease service called Bugaboo Flex that lets customers upgrade and ultimately return strollers.

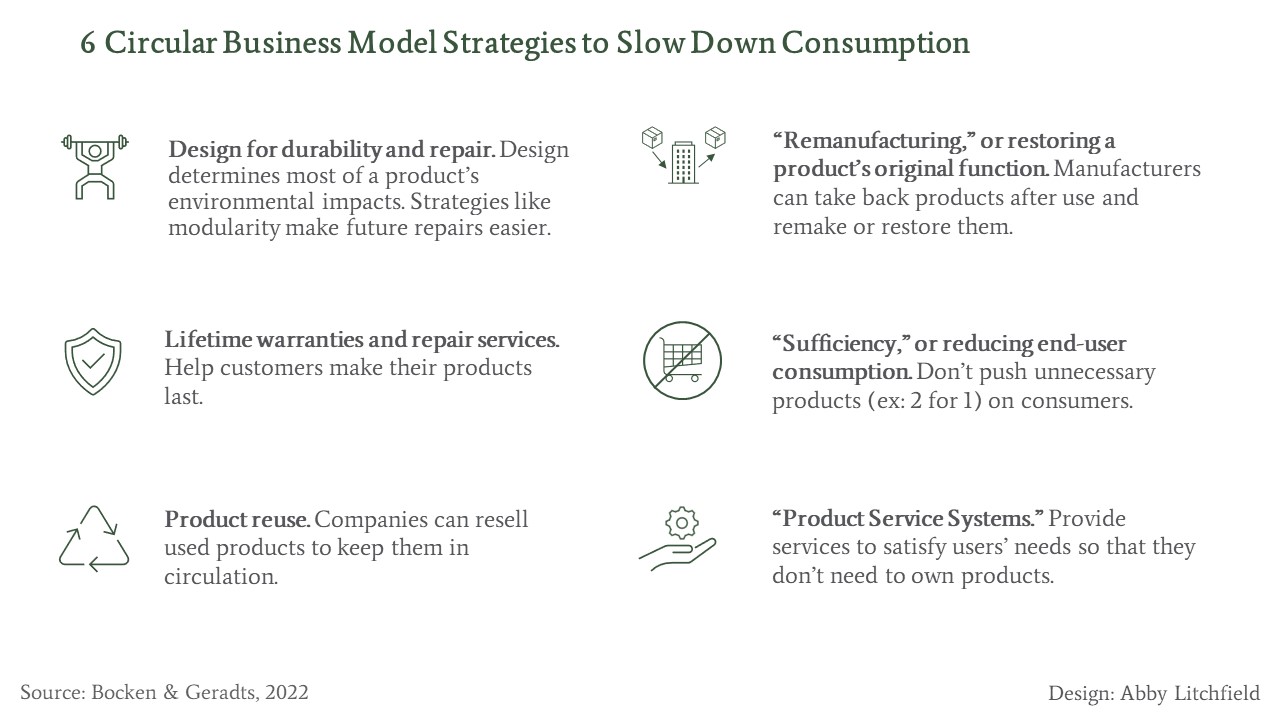

But most business models that slow the loop relate to extending product value and life. Here are some ways this is done:

- Design for durability and repair. Most of a product’s environmental impacts are determined in the design phase. Circular design strategies include making part replacement easy; this is sometimes called “modularity” or “deconstructability.”

- Lifetime warranties and repair services. Products get fixed instead of thrown away. For example, electronics company Philips offers repair options as a way to make medical equipment last.

- Product reuse. Products can find new owners through platforms like eBay or through manufacturer and retailer efforts — for example, furniture company IKEA offers a buyback and resell service.

- “Remanufacturing,” or restoring a product’s original function. Manufacturers or third parties can remake products and return them to original function. This happens with products from cellphones to engines.

There’s also “Sufficiency,” or reducing end-user consumption. What if society just consumed less? One pathway is marketing that doesn’t “oversell.” For example, no two-for-one offers or constantly-changing products. Furniture company Vitsoe aims to provide furniture that’s “better rather than newer.”

Regenerate the Loop

Regeneration finds ways to restore or revive the original resource – the natural environment. Companies use ‘net positive’ strategies to improve the environment they have affected, perhaps by remediating soil. They also try to eliminate toxic substances in production.

Regenerative business models are still emerging. They try to provide value to human and non-human stakeholders through fairness, partnerships with nature, and leadership aligned with these principles (Bocken et al., 2023). An example: Food company Danone supports regenerative agriculture among its farmers by providing subsidies and guidance.

Advantages and Disadvantages of Different Circular Business Models

If these are all possible business models, which should companies pursue?

Years of research, including interviews with hundreds of managers, provide an assessment of these approaches’ economic and environmental potential. Descriptions below draw particularly on a 2021 article for the Stanford Social Innovation Review and a 2021 report for the WWF.

These can be complex actions taking place in varied settings, so it’s tough to generalize. But here are the high-level take-homes.

Slowing the Loop: Reducing Consumption and Extending Product Life

Environmentally, this is “potentially the most impactful environmental strategy,” according to the researchers. “But it’s also the most challenging one to implement because it requires a significant rethink of the business model.”

“Slowing” requires focusing on “value over volume” and moving from faster to slower types of consumption. Companies may charge a “premium” upfront price, which covers long-term service. With a “Product Service System,” they can price per unit of service – and may lock in repeat customers. Companies may have lower material costs (fewer products), though higher labour and logistics costs. They may need to change product design and contract with external repair services.

Some customers value longevity, better warranties, repairs, and maintenance. But others prefer novelty. Rental models can be a way to address this, allowing consumers to exchange items after relatively few uses.

Narrowing Resource Loops: Efficiency and Sustainable Inputs

Efficiency strategies can provide clear payoffs with little change to broader business models. Actions as simple as changing light bulbs save money and provide environmental benefits. For example, Unilever saved more than €873 million by improving energy efficiency across its factories.

Substituting more sustainable inputs – whether less toxic chemicals or local materials – can increase production costs and pricing. As with many circular economy strategies, there may be benefits in terms of reputation and customer interest.

Closing Resource Loops: Recycling and Industrial Symbiosis

Recycling has real but limited impact. Environmentally, it’s not enough to address resource use. Even if all waste could be recycled this would only cover one-fifth of the current material requirements.

Here are additional economic and environmental challenges with recycling:

- Primary raw materials are often cheaper than secondary (recycled) raw materials.

- For major global manufacturing materials like steel, cement, paper, glass, plastic and aluminium, recycling is complex and energy saving effects are less clear.

- Materials can get contaminated and lose quality through recycling.

Industrial symbiosis offers a higher value proposition. Companies exchange waste (or use it internally) to create higher-value items. British Sugar’s strategies for reusing waste “delivered efficiency and productivity improvements and diversified revenue growth,” Bocken and colleagues write. As much as 25% of the firm’s revenue came from its waste-driven product lines – along with tremendous ecological benefits.

Regenerating Resource Loops: Restoring the Environment

Regeneration makes sense environmentally. It’s hard to argue with restoring the environment.

Does it make economic sense? At the most fundamental level, “there’s no business on a dead planet.” Regeneration can have reputational benefits, creating goodwill among customers, communities, and NGOs. Such stakeholder relationships have real economic impact.

There can be direct economic benefits as well. For example: Unilever has seen better soil and more pollinators from its regenerative agriculture projects. But higher yields and higher profits can take time.

A Circular Economy that Creates Transformation

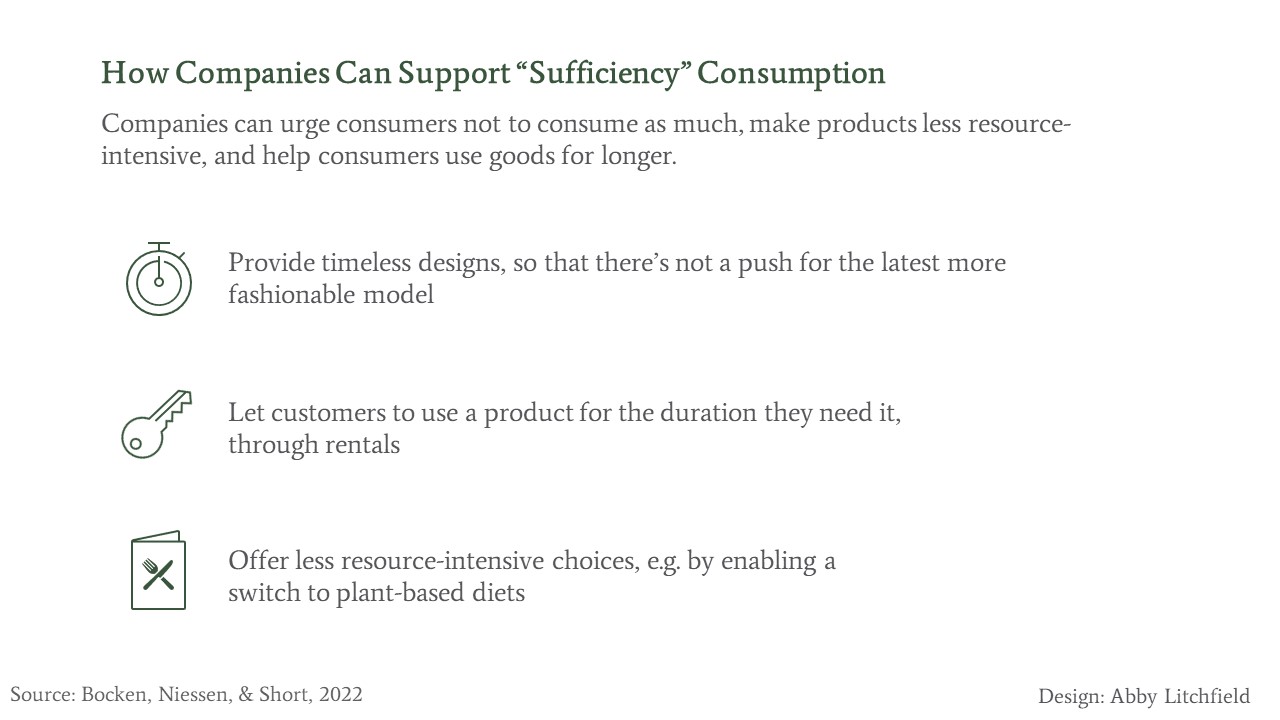

The “sufficiency-based” circular economy is the focus of Bocken’s most recent work. That’s a model of “Slowing the loop” where users consume less.

People have “enough to live well without excess, satisfying essential needs necessary to live and function comfortably, while prioritizing quality of life in work, education, and leisure, but not needlessly striving to satisfy infinite human material wants,” write Bocken and co-authors Laura Niessen and Samuel.

Consumers and companies could help create this world. Companies could urge consumers not to consume as much, make products less resource-intensive, and help consumers use goods for longer. They might:

- Provide timeless designs, so that there’s not a push for the latest more fashionable model.

- Let customers use a product for the duration they need it, through rentals

- Offer less resource-intensive choices, e.g. by enabling a switch to plant-based diets

It’s not a path to going out of business. Such businesses can take market share away from others that produce less durable and sustainable products. But it may not be a path to dramatic growth, either. For example: Appliance company Miele guarantees its washing machines for 20 years, in an industry where the average lifetime is 10 years. Miele accepts a modest growth rate, according to a 2010 report, in order to protect its sustainability priorities.

Transformation Requires Societal – and Political – Involvement

Many factors could spur greater support for the circular economy. Resource scarcity, for example, can drive change. But government intervention is likely also necessary. Right now, the circular economy transition may be difficult for companies. Despite the potential, it can be confusing and even risky. But what if companies…

- Received public innovation funds and procurement opportunities for circular practices

- Could access a knowledge hub for guidance and mentoring

- Faced requirements like full environmental liability or restrictions on environmentally unsustainable practices (such as single-use items)

These might create an equal playing field across companies and tip market incentives toward circular economy business models – and a better world for all.

More info