Modern Housing. An Environmental Common Good

Housing is a fundamental human right, our core social foundation. As such, housing intrinsically integrates the challenges of both social and environmental justice. Yet its current trajectory, defined by financialisation, extraction and inequality, mitigates against achieving either goal. We are at a critical juncture as a result, and we must fundamentally rethink our approach to housing. Could we

reverse our extractive approaches in order to produce housing that is dignified, durable, beautiful and adaptable, and made available for all, as a common good? And could the way that we make common good housing happen also produce clean, safe, healthy, convivial and nourishing shared environments? A coherent strategy would see the interdependent dynamics of making housing – building and retrofitting – realigned, redeployed and interconnected across an integrated global approach, and redefined by a revived common good framework. It would recognise that the way these dynamics play out in the Global North directly affects the Global South and vice versa, and that this symbiotic, entangled relationship must work within planetary boundaries. It would recognise the right to housing, but also the rights of the environment. It would recognise the right of people to remain in place, as well as the increasing need to fulfil migrants’ rights to housing.

This requires a transformation in practices around housing in terms of design, construction, care, economy, and more diverse forms of shared living, tenure, ownership and governance. At the larger scale, the industry behind housing must shift towards retrofit, reuse and redistribute, cultivating new and old skills with circular materials from regenerative sources designed for assembly and disassembly via modular fabrication. At the smaller scale, genuine participation in making and re-making housing can be unlocked through self-build, adaptive, open building systems. A redistribution of existing living spaces must meaningfully counterpoint

the extractive practices of building. In all this, engaged, publicly led planning and policy can be complemented by a revived public and social housing, which can create and direct sustainable and affordable housing markets outside extractive financialisation.

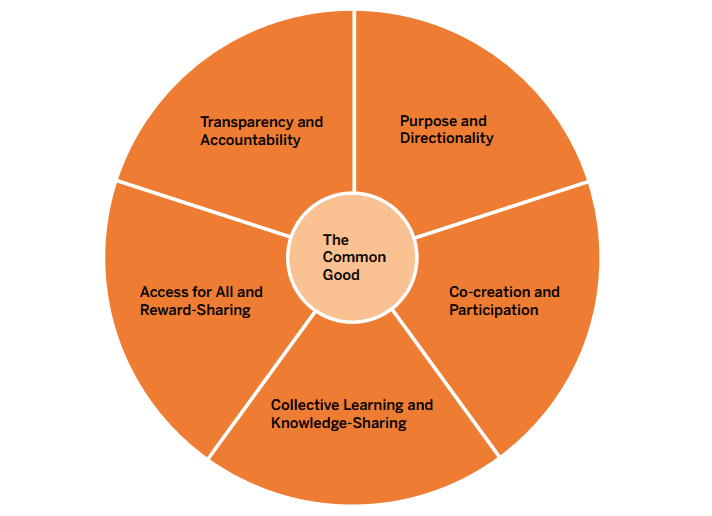

Housing policy and practice could powerfully articulate and demonstrate a new policy framework for ‘reviving the common good.’ This would be oriented towards the rights of the environment as well as people, and based around principles of purpose and directionality, co-creation and participation, collective learning and knowledge-sharing, access and reward-sharing for all risk-takers, as well as transparency and accountability in decision-making.