International drivers of low carbon structural design

News Detail

Source:

The Institution of Structural EngineersSynopsis

Environmental certification schemes have historically required carbon assessment on projects, but their effectiveness as a tool for promoting low carbon design is often limited. The world’s major economies have established legislation in an effort to achieve net zero greenhouse gas emissions and combat climate change. To meet these commitments, national governments are regulating carbon emissions in the construction industry, with some regulations in place or in the pipeline. Investors are prioritizing low carbon projects, and developers and building operators are aligning their business models with these goals, including requirements for embodied carbon in their sustainability briefs.

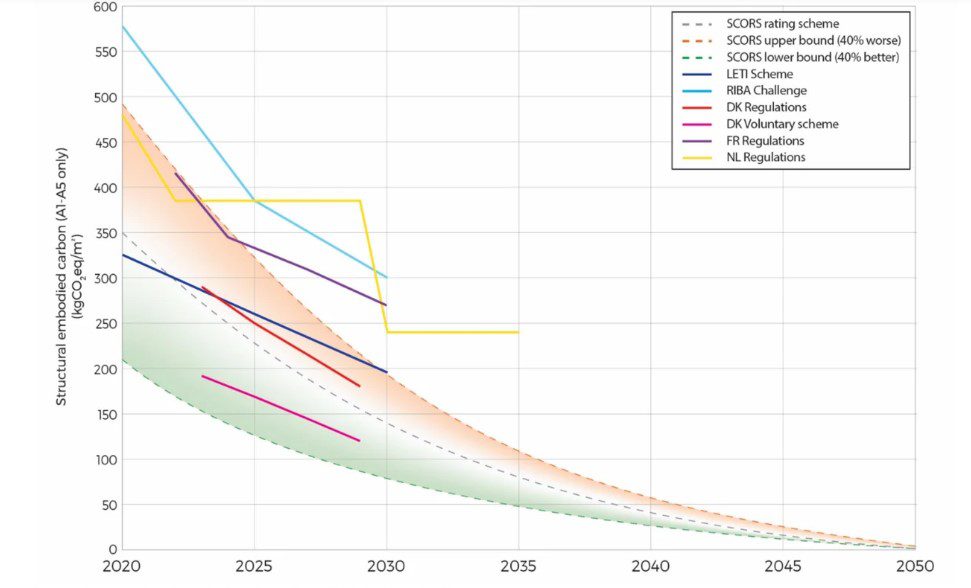

In the coming decade, structural engineers have the opportunity to lead the way in this transition towards a low-carbon built environment, but immediate action is needed to measure and reduce carbon on a project level before regulations catch up. In this article we highlight international best practice examples of drivers for low carbon design. Sharing knowledge and best practice across borders allows us to develop and innovate in step at an international level.

Certification schemes

Historically, environmental certification schemes have been the main driver of using life cycle assessment (LCA) to quantify embodied carbon emissions associated with buildings. They can therefore in theory be a driver for implementation of low carbon design on projects. Most environmental certification schemes require some form of life cycle assessment to be undertaken (Jensen & Birgisdottir, 2018). While not mandatory, achieving the highest levels of certification is challenging without LCA. Local planning authorities may mandate certification (BRE, 2021) and institution or publicly funded projects often have minimum compliance levels. However, the adoption of certification across construction internationally varies widely.

One of the most critical decisions a structural engineer can support a client and design team in making is whether a new building is required at all. The hierarchy of ’build nothing > build less > build clever’ strongly encourages a “refurbish first” approach. Many of the most common environmental certification schemes only award from concept design onwards, by which point this crucial choice has already been made, and the substantial benefits of the choice are not recognised.

In the UK BREEAM NC 2018 awards a significant number (~7%) of materials credits for integration of Life Cycle Assessment methodologies at concept design and technical design stages (BRE, 2018). Credits are awarded based on design option studies being undertaken and the environmental impact of each studied during the relevant design stages. However, the scheme does not require specific targets to be met or even that the lowest carbon option is selected. The accuracy and rigour necessary for a whole building study also makes it time consuming to carry out, and the LCA results often ‘lag behind’ the current considerations of the design team by weeks. It is debateable therefore how much the certification in its current form influences design decisions and leads to low carbon outcomes.

LEED BD+C v4.1 is widely used in the US and Canada. It goes somewhat further than BREEAM, with the materials credit requiring LCA studies across a wide variety of indicators and not only global warming potential (US Green Building Council, 2018). It also awards credits based on a demonstrable reduction of impact from the design process through to construction on site. A 20% reduction in carbon, 10% reduction in other impact categories, and re-use or salvaged materials gives the maximum score. Anecdotally many clients consider ‘cost per credit’ when achieving a certain level of accreditation, meaning that this credit is often not pursued.

Singapore’s Green Mark is a voluntary certification scheme with credits awarded to a variety of sustainable buildings categories (Building and Construction Authority, 2021). For the whole life carbon credit CN1 the 2021 edition awards credits for undertaking whole life carbon assessment of the project. Unlike most other certification schemes, it sets maximum embodied carbon rates (A1-A4) for the superstructure, ranging from 1000-2500 kgCO2e/m2 depending on building usage. Further credits are awarded for buildings that achieve 10% and 30% below these rates. The relatively high carbon targets compared to European legislation (refer to part 2) are reflective of Singapore’s unique construction constraints. Limited land and prevalence of concrete in construction result in high rise, high carbon buildings.

The DGNB system is widely used in Germany and Denmark, and puts equal weighting on social, economic and environmental factors in its evaluation (DGNB, 2020). Credit ENV1.1 awards points for undertaking life cycle assessment during the design process, using it for building optimisation, and for buildings that beat specific targets (9.4 kgCO2e/m2/yr, 470 kgCO2e/m2 over 50yrs). The highest grade is awarded to buildings that achieve a >45% reduction on these target values. It also covers other indicators beside global warming potential, although GWP is still given the most weighting. In principle this therefore incentivises ‘good’ low carbon design.

In conclusion, environmental certification schemes can be a useful tool for encouraging low carbon design in the construction industry, but their effectiveness varies. Many schemes only award credits from the concept design stage onwards, meaning that the decision to refurbish an existing building rather than construct a new one is not recognized. In addition, certification schemes require an informed client willing to pursue certification. Consequently, certification schemes on their own do not appear to be a major driver for low carbon design as they only target a small subset of the construction industry, and overlook decisions made when establishing a project brief.