Sunflower House/

Koichi Takada Architects

Project Details

Location(City/Country):

Le Marche / Italy

Tipology:

Concept Design Residential

Year (Design/Construction):

2020 / -

Area (Net/Gross):

- / 150 m2

Operational Carbon emissions (B6) kgCO2e/m2/y:

0

Embodied Carbon emissions (A1-A3) kgCO2e/m2:

0- A Life Cycle Analysis (LCA) will be performed to inform material selection in the relevant regions where it will be built.

- The design intent is to use a combination of local low carbon materials.

- The building is elevated from the ground to minimise interference with the biodiversity of its surroundings.

- Rainwater is collected and used for irrigation and toilet flushing.

- The roof rotates to maximize solar panel energy production.

Project description as provided by the architects.

Koichi Takada has a bold vision for the future of architecture, powered by the ancient wisdom of nature. As a global leader in sustainable design, Takada has been commissioned by Bloomberg Green to imagine the dream home of Europe’s greener tomorrow, and the answer to this challange is the Sunflower House.

One century since the Bauhaus reshaped the West through their modernist designs, Takada has been recruited to help create a new common aesthetic born of the urgent need to combat climate change.

Bloomberg Green: The New European Bauhaus gained gravitas following a speech in October by the president of the European Union, Ursula von der Leyen, who called for a new climate project with “its own aesthetics, blending design and sustainability” and proclaimed “a new European Bauhaus movement” was required.

Takada’s response to that challenge is Sunflower House, a Carbon Positive single-family dwelling inspired by the distinctive yellow flower and powered by the sun.

“Climate change must be a catalyst for positive change, beginning with our humble homes,” says the Tokyo-born architect based in Sydney.

The original Bauhaus, an early 20th century collective of designers and craftspeople, is behind much of what we recognize today as modern architecture—clean, sleek, hard. “For the future of the planet we must shift from industrial to natural. We need a kinetic, living architecture that respects the environment while enhancing the wellbeing of the humans who inhabit it” says Takada.

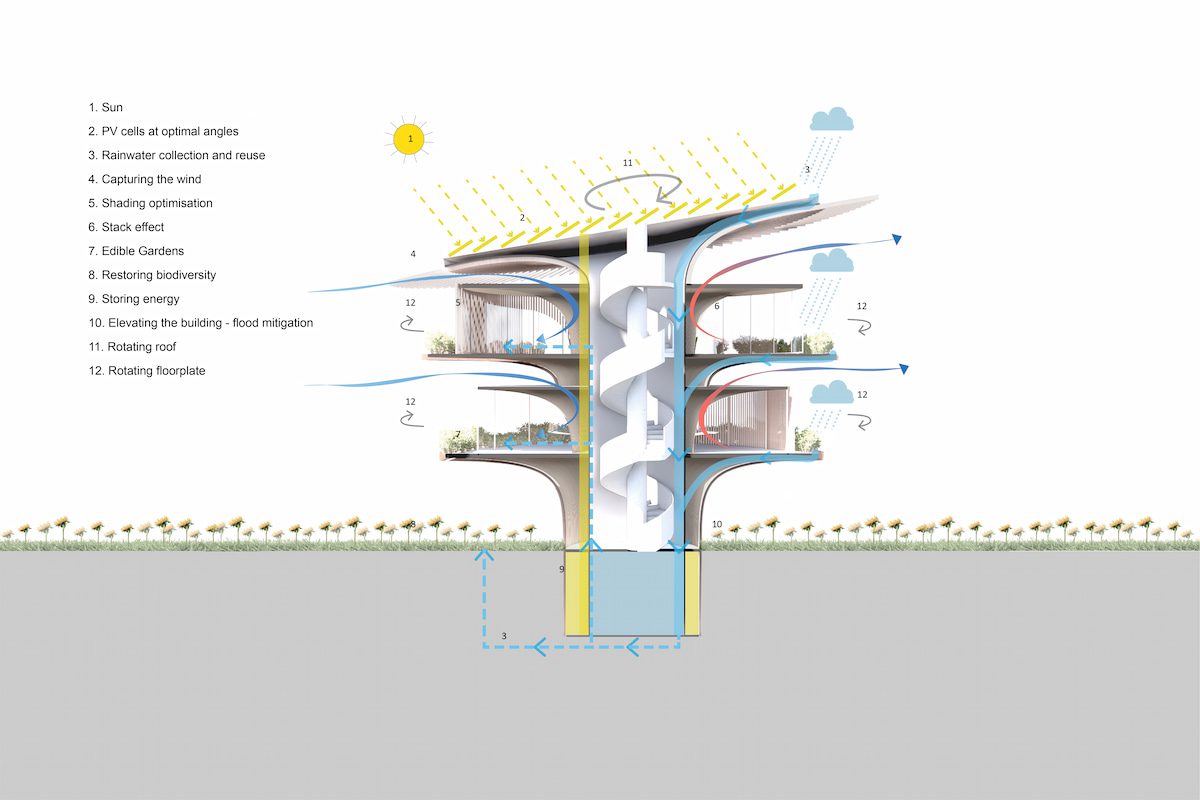

Sunflower House is designed for the Italian region of Umbria, renowned for its rolling farmland and yellow fields of sunflowers, where heat waves are becoming more frequent and extreme. Elevated from the ground to minimise interference with the biodiversity of its surroundings, the solar panels on its petaled roof rotate on sensors for maximum sun exposure.

“Artificial structures require large foundations, but with sunflowers nature achieves a beautiful balancing act,” says Takada. “There is minimum intervention on the ground so the earth has room for other activities, yet the sunflower magically nods its head to bathe in the light. The Italian word girasole literally means ‘turn to the sun’.”

The circular structure of Sunflower House rotates around a central “stem” to follow the sun, allowing the moving “disc florets” to produce up to 40% more energy than static panels. Energy that isn’t used can be fed onto the grid or stored in battery “seeds” and rainwater is collected and used for irrigation and toilet flushing. The perimeter around the roof shades the windows below and aids in ventilation, and a secondary rotating mechanism over the glass walls protects the building from solar radiation.

“For the Bauhaus form followed function, but we say form follows nature,” says Takada.

Each floor of Sunflower House hosts a two- or three-bedroom apartment, and each building can be as high as three stories. Scalability opens up the possibility of creating a climate-positive neighbourhood inspired by sunflower fields, in which the plants self-organise, unfurling in a zigzag pattern to avoid overcrowding and maximise exposure to sunlight.

“Designers and architects talk about drawing inspiration from nature in an aesthetic sense but we must go much deeper than that,” says Takada. “It’s not just about making a building look natural, it’s about creating positive environmental change in the homes we live in, the neighbourhoods we work and play in, and ultimately the planet we are privileged to inhabit,” says Takada.